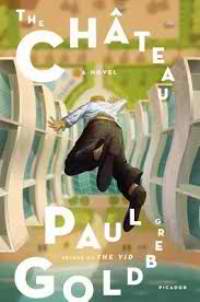

The Château by Paul Goldberg

Monday, April 2, 2018 at 7:54AM

Monday, April 2, 2018 at 7:54AM

Published by Picador on February 13, 2018

A cosmetic surgeon known as the Butt God plunges to his death. His college roommate, Bill Katzenelenbogen, recently fired from his gig as an investigative science reporter for the Washington Post, decides the death might merit a book, perhaps jumpstarting a new career. Bill was fired for insubordination, meaning he didn’t give a hoot about any of the stories he’d written during the last six years. He was one of the typing dead.

Bill needs the book to succeed because he has no income and, thanks to an unfortunate divorce, no savings. The book project forces Bill to reunite with his father (with no salary, Bill can’t afford a Ft. Lauderdale hotel) and to meet his stepmother Nell for the first time. His father (along with many other established immigrants who, having achieved modest wealth, hates new immigrants) lives in Château Sedan Nueve. His name is Melsor and he acquired his wealth through one of his shady operations, this one involving Medicaid fraud, of which he was acquitted.

Bill’s relationship with his father was never strong, but it deteriorated rapidly twenty years earlier after Melsor ignored Bill’s warning about a “miraculous” cancer treatment that killed Bill’s mother. The choice of doctor was one of many stop signs that Melsor spent his life barreling through.

Bill’s social, political, and religious observations as he muddles through his newly unemployed life are darkly amusing. He also expresses entertaining and wide-ranging opinions about relationships, interior design, Russian poetry, Russian vodka, aging, sex, aging sex, truth as an irrelevant virtue, global warming, real and fake news, fascism, and any number of other topics.

Bill’s father is even more hilarious. His philosophy is an eclectic assemblage of maxims from Russian poetry, Donal’d Tramp’s The Art of the Deal, and an amalgam of American and Russian ideals that have been conveniently edited to support his own financial interests. He is at war with the corrupt condominium Board that, in his view, is selling out the Château residents by accepting kickbacks in exchange for shoddy and needless construction that will increase the residents’ fees with no corresponding benefit. Whether his suspicions are true is both unclear and irrelevant, because believing them to be true fits Melsor’s jaded view of the world.

The story ends in ambiguity that highlights the ambiguous nature of the modern world. Readers who can’t bear any criticism of Trump will no doubt vilify Paul Goldberg as a liberal, that most detested of creatures, but the novel actually has little to do with Trump or American politics. It is more about American life, as seen through the lens of two perspectives: a Russian Jewish immigrant and his Americanized son, neither of whom have managed to live perfect lives but both of whom have strong opinions that readers are free to test with an open mind. To the extent that the novel criticizes the president, it does so lightly.

The story’s humor, and particularly its send-up of Florida condominium boards (which, according to a local journalist, are all assumed to be filled with corrupt back-biters and therefore evidence of corruption isn't newsworthy), kept me laughing consistently. The central characters have the kind of quirks that bring them to life, but they aren't based solely on stereotypes. The Château won’t appeal to every sense of humor (or to people who have no sense of humor), but it appealed greatly to mine.

RECOMMENDED