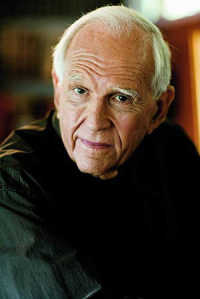

Harlan Ellison

Tuesday, December 27, 2022 at 5:44AM

Tuesday, December 27, 2022 at 5:44AM

A cranky, cantankerous curmudgeon who inspired awe and derision, Harlan Ellison is known for writing award-winning stories in fantasy and science fiction, assembling two brilliant anthologies of original science fiction stories, and writing the script for the best episode of the original Star Trek series. In my teens and early twenties, I devoured Ellison’s work, including two volumes of essays (The Glass Teat and The Other Glass Teat) that shaped my view of how a life should be lived. Ellison made some mistakes in his own life (who hasn’t?), but his commitment to artistic integrity — which included removing his name from scripts when producers meddled with them, including the Star Trek script — never wavered.

Ellison died in 2018 at the age of 84, four years after a debilitating stroke. During his lifetime, he was criticized for inappropriate behavior that is briefly summarized in his Wikipedia entry. Ellison was surely flawed, but his best work hits readers with the power of a punch to the gut. He sliced into the darkest essence of human nature and evoked the kind of genuine emotion that most writers can only dream of creating.

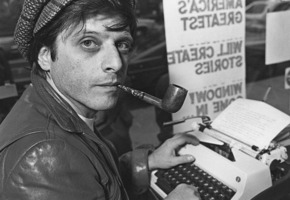

Ellison was known for his showmanship. He sat in bookstore windows and pounded out short stories on his typewriter. He was an occasional guest on Tom Snyder’s talk show, using the opportunity to riff on whatever subject happened to be bothering him that day (something was always bothering Ellison). He liked to tell the story of being fired by Walt Disney Company on his first day when he made a speech in the commissary about a pornographic film starring Mickey and Minnie that he wanted to write. He also talked about working as a runner for mobsters when he was growing up in Cleveland. His life was colorful and sometimes sad, but I doubt he could have lived it any differently.

Ellison loved dogs, for which all his sins are forgiven.

Make of his life what you will, Ellison was a hell of a writer. Standout stories that live in my memory include the novella “A Boy and His Dog,” “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” “The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World,” “Jeffty is Five,” “‘Repent Harlequin,’ Said the Ticktock Man,” and “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs.” In addition to the Star Trek episode “The City at the Edge of Forever,” Ellison wrote an episode of The Outer Limits (“Soldier”) that, after litigation, was acknowledged as the original version of James Cameron’s Terminator movie. He also wrote a better screenplay for I, Robot than the version that was filmed, but Warner Brothers fired him when he told an executive (justly, no doubt) that he had the intellectual capacity of an artichoke.

Younger readers who encounter Ellison’s stories for the first time might dismiss them as unoriginal. When Ellison wrote them, they were completely original. They seem familiar today because so many writers in print and film who riffed on Ellison’s ideas owe their inspiration to his visionary stories.

As an editor, Ellison anthologized original stories in Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions, the best collections of original sf stories I’ve ever found. He accepted stories for The Last Dangerous Visions but never finished the project, causing more controversy by tying up the publication rights.

Ellison’s New York Times obituary provides a nutshell summary of a remarkable life.

Ellison was so prolific that the bibliography on his website is incomplete, despite its length.

Harlan Ellison works reviewed on Tzer Island are:

Deathbird Stories (first published in 1975, republished in 2014) – one of a half dozen collections of Ellison’s short stories that I regard as essential reading for science fiction fans.

Blood’s a Rover (2018, edited by Jason Davis) – the novella “A Boy and His Dog” is collected with a couple of related stories and an unproduced screenplay for a television pilot.

Night and the Enemy (first published in 1987, republished in 2015) – a graphic version of early Ellison stories, of primary interest to Ellison completists.

Harlan Ellison’s 7 Against Chaos (2013) by Paul Chadwick – a graphic novel published by DC that Ellison plotted, with art and most of the dialog contributed by Chadwick.