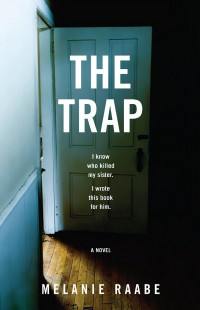

The Trap by Melanie Raabe

Wednesday, August 10, 2016 at 9:37AM

Wednesday, August 10, 2016 at 9:37AM

Published by Grand Central Publishing on July 5, 2016

Linda Conrads is the pen name of a successful literary author. She was traumatized after witnessing the death of her sister. She’s 38 and hasn’t set foot outside her house in more than a decade. She lives in her own dark world, which is sometimes invaded by the face of her sister’s assailant. Her troubled life becomes worse when she sees the killer on television. He is, it seems, a news reporter named Victor Lenzen.

Conrads does not think the police will believe her (they didn’t before) so she decides to set a trap in order to expose Lenzen’s guilt. As a reclusive celebrity, she knows the reporter would seize the chance to interview her in her home. First, she needs to write a crime novel that is based on her sister’s death so that Lenzen will have something to ask her about. At the same time, she hopes that Lenzen recognizes the crime he committed when he reads the book, giving him an additional motivation to come to her house for the interview. The book -- excepts of which appear at regular intervals -- is too cheesy to take seriously as the work of a respected author.

Melanie Raabe never quite convinced me that Conrads’ decision to deal with Lenzen on her own terms, rather than calling the police, was credible. True, the police might have doubts about her credibility, but she had little reason to forego their involvement or to fear that a public figure like Lenzen would retaliate against her largely nonexistent “loved ones” because she identified him to the police.

In any event, the interview does not go as Conrads planned, although it gives her an opportunity to reflect upon her relationship with her sister, one that he idealized in the book and in her memory. Whether Lenzen is or is not the guilty party becomes the novel’s driving mystery.

The plot is contrived and the ending is predictable. I wasn’t surprised by it and I didn’t believe it. That’s a poor combination. A weak love story that doesn’t develop until the novel is nearly over is also contrived and predictable.

There are also too many “cheats” during the story. The worst example: a chapter ends with a shock and the next chapter tells us that the shocking event was imagined, not real. That’s a cheap way to build suspense, but none of the suspense-building efforts succeed in The Trap.

Raabe’s prose (translated by Imogen Taylor) is graceful. Her portrayal of the reclusive author is convincing. Those attributes make the story easy to read. With so many better choices available to fans of crime fiction, however, I question whether The Trap is worth a reader’s time.

NOT RECOMMENDED