Will Eisner's The Spirit: Who Killed The Spirit? by Matt Wagner and Dan Schkade

Monday, October 24, 2016 at 9:22AM

Monday, October 24, 2016 at 9:22AM

Published by Dynamite Entertainment on October 25, 2016

Will Eisner was the most accomplished graphic storyteller of his generation. He is best known for The Spirit, a series that ran from 1940 to 1952. His multi-page stories, published in Sunday newspapers, came to be known as “the Spirit section.”

Eisner’s innovative approach to the series set him apart from other cartoonists of the time. He wrote adult fiction with mature themes (subject to the constraints of his time and audience), putting a mask on his detective only to accommodate publishers who wanted a costumed hero. He gave his detective a rumpled look and used shadows to convey a gritty, noir sense of the city he served. His detailed backgrounds often showed derelicts, clotheslines, and the detritus of urban decay. His perspective was cinematic, constantly changing, showing the scene from a variety of angles and distances. He gave new shapes to the standard square panels that defined comic art. He even transformed The Spirit logo with each story, making it a part of the background (the letters spelled out in blowing bits of paper, appearing on a billboard, or squeezed together to form a towering building).

Eisner’s stories were deeply humanistic. He often used humor to expose greed and corruption. Clearly influenced by his experience of anti-Semitism, Eisner depicted the struggles of ordinary people, sometimes making them the story’s focus while relegating the Spirit to a background role.

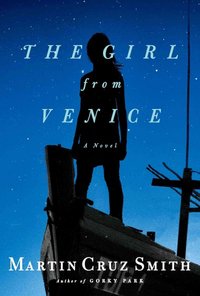

Written by Matt Wagner and drawn by Dan Schkade (with covers contributed by several other artists), Who Killed the Spirit? is intended as a 75th anniversary celebration of Eisner’s series. If it isn’t quite Eisner in the depth of its storytelling, that’s to be expected. Nobody is Eisner. The volume is nevertheless a worthy tribute to Will Eisner’s iconic hero.

The Spirit is dead … or is he? Dolan thinks Denny Colt has been dead and buried for two years (really dead, this time) until he gets a return visit from the Spirit. Meanwhile, detectives Sammy Strunk and Ebony White (redrawn to avoid Eisner’s racial stereotyping) decide to find out why the Spirit has disappeared.

The Spirit himself explains why he disappeared, although it’s all kind of a mystery to him ... and mysteries, of course, need to be solved. He begins with an overheard name, Mikado Vaas. From his underworld interrogations, he learns that Vaas is something like Keyser Söze -- more myth than man. And then there’s the mysterious woman who occasionally appeared to gaze at him in his captivity.

Along the way, The Spirit encounters familiar enemies like the Octopus and woos Dolan’s shapely daughter as Dolan decides whether he really wants to retire, turning the police commissioner’s job over to a politically connected boob. The story is long, unlike traditional Spirit stories, but it has all the elements of a Will Eisner story. It is consistently entertaining.

In fact, from the standpoint of writing and particularly the art, this homage to The Spirit channels Eisner faithfully. It almost feels like a story Eisner could have done, and that’s high praise.

RECOMMENDED