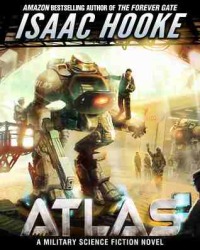

ATLAS by Isaac Hooke

Friday, November 14, 2014 at 9:20AM

Friday, November 14, 2014 at 9:20AM

Self-published in 2013; published digitally by Amazon Digital Services on May 27, 2014

The opening chapters of ATLAS are promising. The novel is set in the near future. While the future is loaded with standard sf backdrops (robots, flying cars, glasses that function as wireless computers, embedded ID chips), Isaac Hooke sets the scene in meticulous and convincing detail. Unfortunately, all of that ends up being wasted.

Crossing the border to the United Countries (apparently the US and Canada) seems like a ticket to the good life, except for the catch: forced military service for immigrants. Anxious to put a dangerous and wasted life behind him, Rade Galaal enters the UC with his mentor Alejandro Mondego and new friend Taho Eaglehide. Rade wants to prove himself by joining the Navy's special operations division -- MOTH -- which is a space-faring version of the SEALs.

The story is narrated in a relaxed, unpretentious, first person voice. The writing style -- short sentences and a lot of single-sentence paragraphs -- follows a popular formula for fast-paced action novels. It works reasonably well, apart from occasional asides to explain a physics problem. The novel's problems have more to do with content than style.

Some scenes are much too familiar, to the point of being clichéd and trite. Basic training is filled with pushups and abusive drill instructors. MOTH training begins with the classic "Look to your left, look to your right, those people won't be here at the end." The story even has the "Ring the bell when you want to quit" scene from G.I. Jane. In fact, much of the first third of ATLAS seems like a prose version of G.I. Jane without the Demi Moore character (women being conspicuously absent from the MOTH ranks). You'd think an imaginative sf writer would imagine a future military that figured out a better way to train soldiers, but writers seem to enjoy regurgitating the twentieth century "abuse makes men tough" model. Fortunately the scenes move quickly.

Rade joins MOTH to see if he can "become a man." Becoming a man means you learn to endure a lot of abuse, to operate high tech weaponry, to clobber everyone you fight, and to bang a female when you get a chance. That's a fairly superficial mindset (although one that is popular with teenage boys) and I hoped that Rade would grow out of it before the novel ended. He doesn't.

Rade's dedication to the MOTHs also compels him to indulge in page after page of dumbed-down versions of the St. Crispin's Day speech. The "valiant brothers in arms" theme is way too heavy-handed. ATLAS is not a novel of subtle thought.

After we get through the familiar training scenes, the novel advances to familiar "the aliens just wouldn't stop coming" scenes. Many of those scenes reminded me of Armor, substituting crab aliens for ant aliens and skipping the depth of character that makes Armor a better book. Still, the novel improves considerably after the fighting starts. As a fast-moving action story, some aspects of ATLAS are enjoyable, but the novel is so derivative and unimaginative that readers would be better served by investing their time in better examples of military sf.

NOT RECOMMENDED