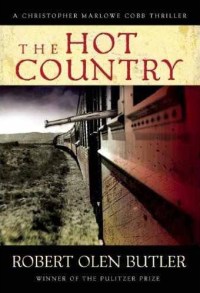

The Hot Country by Robert Olen Butler

Friday, October 5, 2012 at 8:52AM

Friday, October 5, 2012 at 8:52AM

Published by Mysterious Press on October 2, 2012

Robert Olen Butler returns Pancho Villa to life as a supporting character in his latest novel. The Hot Country follows a literary path marked by Graham Greene (among others) -- within the trappings of a thriller, the author undertakes a deeper study of human nature. The "hot" country is Mexico in 1914: hot because of its climate, because it is a hotbed of revolution, because its women are passionate. The result is entertaining but not as compelling as Greene's best novels -- or Butler's.

On the day when the United States begins its military occupation of Vera Cruz, a news photographer snaps a picture of Christopher "Kit" Cobb, a reporter for a Chicago newspaper, standing near two dead Mexican snipers. The story jumps ahead a few weeks as Cobb gazes at the photograph in his editor's office, remembering the woman in the picture, Luisa Morales. It then moves back in time to the day Cobb met Luisa, shortly before the Marines arrived in Vera Cruz. The remainder of the novel covers the time that passes between the day of the invasion and the day Cobb returns to Chicago, then moves forward another few days.

Cobb is intrigued by Luisa, even as he comes to suspect her as the sniper in nonfatal shootings of a Mexican priest, a city official who is cooperating with the Americans, and an American Marine. While he wants to pursue the story of the shootings, he's also intrigued by the tall scarred German he sees sneaking ashore from the Ypiranga, a German steamer. During most of that novel, Cobb is chasing a dangerous story that focuses on the scarred man, Friedrich von Mensinger, a representative of Germany who wants to persuade Pancho Villa to launch a counterattack against American forces.

Butler avoids the improbable shootouts and one-against-five martial arts battles that are commonplace in ordinary thrillers. There is a knife fight, there is a gunfight, there's even a sword fight, but they are realistic -- they always convey the sense that Cobb's life is at risk. Most of the time, Butler creates tension with more subtlety: using a fake passport on a train, Cobb must persuade the Federales that he is a German; searching through Mensinger's saddlebags for hidden documents, Cobb is hyperaware of the sounds that signal danger.

Still, in his attempt to meld a literary novel and a thriller, Butler doesn't fully succeed in the creation of either one. The final scene in Mexico is enjoyable but unconvincing, while the novel's final scene (a revelation about Cobb's mother) is from well beyond left field. Key characters have the feel of stereotypes: an embittered news photographer who stopped writing (and started drinking) as a protest against censorship; an American mercenary who has signed on to support Pancho Villa's cause. We spend too little time getting to know Luisa and Mensinger and Villa. Although Cobb could have stepped out of a Graham Greene novel, Butler doesn't quite capture the tortured soul that makes Greene's central characters so memorable.

This is not to say that Cobb is the empty shell that so often characterizes a thriller hero. Cobb describes himself as "a gringo with imperialist politics and moral indifference," a self-definition he will eventually test. Cobb's relationships with women -- his mother, Luisa, the washer girl who replaces Luisa -- are both complex and superficial. His attempts to communicate with them are muddled; he either fails to speak from his heart or does so at the wrong time.

Butler toughened his prose for this novel without sacrificing its customary elegance. He fills the book with atmosphere, making the reader hears the sounds of war, smell "the complex body-and-equipment stink of fighting men in the field," taste the sourness of pulque. My only stylistic gripe is that during The Hot Country's action sequences, Butler uses run-on sentences to convey Cobb's rush of adrenalin. It is a technique that should be used sparingly, if at all, and one in which Butler overindulges. In all other respects, the prose is stirring, well-suited for a literary thriller.

RECOMMENDED