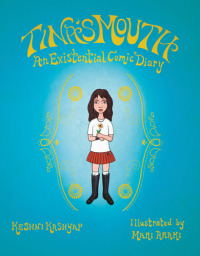

Tina's Mouth by Keshni Kashyap

Friday, December 30, 2011 at 8:33PM

Friday, December 30, 2011 at 8:33PM

Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on January 3, 2012

To fulfill a requirement of her English honors class in existential philosophy, and having rejected the other options as “new age malarkey,” Tina is keeping an “existential diary” that is designed to help her understand who she is and who she is becoming. She considers the project worthy while confessing that she doesn’t care that much. The more immediate question that obsesses her concerns her mouth: particularly, whether she will ever put it to good use by kissing Neil Strumminger.

Tina is fifteen. Her parents are from India. Her father is a cardiologist, her mother a homemaker. She attends Yarborough Academy, which she regards as a fancy name for a high school populated by kids from prosperous families. As befits a teenager, her life is filled with drama. Her best friend has deserted her and she despises the cliques to which all the other students belong. No wonder she finds Sartre appealing. The diary entries, in fact, are written in the form of letters to Sartre.

While the story is cute and often very funny, the question it poses -- “how do you really know who you are?” -- is one of life’s enduring riddles. Tina considers answers that seem superficially true (“Like if I do something stupid at a party and make a fool of myself then that’s me”) but aren’t particularly useful. She considers unoriginal advice (“be true to yourself”) that might be useful but is difficult to implement. Perhaps kissing Neil Strumminger isn’t her purpose in life but it may furnish a clue to life’s meaning. Perhaps (as many believe) the meaning of life is love -- yet, as Tina learns, that notion is easier to embrace when love is fresh, before it leads to heartbreak.

As Tina copes with the daily trauma of teenage life, she puzzles over the difficulty of knowing (much less becoming) “who you are.” Even at fifteen, we are many different things and aspects of our persona are frequently in conflict with each other. Tina writes: “I am east, west, happy, sad, normal, freakish, plain, pretty, Indian, American …. Do you see how complicated it gets?” Tina draws parallels between her life and the lesson taught by Rashomon: there are so many ways of perceiving the truth that an objective truth may be beyond our ken.

Keshni Kashyap avoids simplistic answers to these weighty questions, settling instead for a witty, droll story that dabbles in serious thought without striving for depth. This isn’t intended to be a work of existential drama on the level of No Exit; it’s meant to be a light and humorous look at the existential world from the rather unsophisticated perspective of a bright fifteen year old. Viewed in that light, the novel works.

The diary is illustrated, which effectively makes the book a graphic novel, although some pages are text-heavy while others balance text and art more evenly. I am a better judge of writing than of drawing, but I found the simple illustrations to be interesting and amusing -- the same description I would give to the novel as a whole.

RECOMMENDED