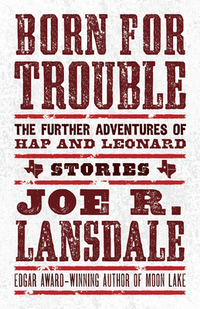

Born for Trouble by Joe R. Lansdale

Monday, March 21, 2022 at 6:14AM

Monday, March 21, 2022 at 6:14AM

Published by Tachyon Publications on March 21, 2022

I always enjoy Joe Lansdale’s stories about Hap Collins and Leonard Pine. I always enjoy anything Lansdale writes. Born for Trouble collects five Hap and Leonard stories. For readers who are unfamiliar with the duo, this is as good a place to start as any. These are excellent tales by a skilled storyteller.

The two longest entries I’ve read and reviewed before. “Coco Butternut” and “Hoodoo Harry” were published in their own volumes.

The other three:

“Sad Onions.” Hap and Leonard come upon a woman in the road who walked away from a single-car accident that killed her husband. The accident doesn’t seem right to Hap or Leonard. Since it is none of their business, they look into it. The wife is young, white, and beautiful. Her dead husband was a wealthy, older black man. The police don’t seem interested. Hap and Leonard uncover a murder plot and make their usual irreverent jokes as they try to avoid becoming the next victims.

“The Briar Patch Boogie” begins with a funny conversation about how perspectives change as we age. On a miserable camping and fishing trip that might have been fun when they were young, Hap and Leonard witness a murder. The killers are guys who make a sport of killing hookers. The story eventually turns into a “Most Dangerous Game” plot, with the twist that the hunters use bows and arrows. The story delivers a true rush of adrenalin.

“Cold Cotton.” Hap’s doctor recommends a once-over by a therapist named Carol Cotton as an alternative to Viagra when Hap isn’t getting the desired results with his wife Brenda. Perhaps Hap is stressed by the evil in the world or by his violent response to it (although he’s made a point of being less violent after moving past his midlife point). Before Hap decides whether to call the therapist, she hires Hap and Leonard (and Brenda and Leonard’s lover Pookie) to provide security in response to threats she’s received. The story takes a couple of unexpected turns and ends with the kind of bloodbath that Hap and Leonard regularly encounter. No wonder Hap needs therapy for his limp organ.

Hap narrates the stories and isn’t shy about sharing his opinions. Like, “in Texas every asshole walks around with a gun and thinks they’re Wyatt Earp.” All the characters, including minor characters, regularly exchange good natured insults; snappy dialog is part of the fun.

These stories reflect aging characters. Hap, at least, is mellowing. Leonard still views violence as a first option when villains deserve a good thrashing (or a good killing), as they usually do. The enduring value of the stories is that Lansdale has imagined a world in which a straight white liberal and a gay black Republican can agree on something — in fact, on most things. Their mutual understanding that human dignity, respectful behavior, and fishing are fundamentally important provide a bond that transcends their political views. Hap and Leonard could be role models for us all (regardless of how we feel about fishing).

RECOMMENDED