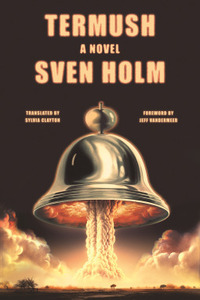

Termush by Sven Holm

Monday, January 8, 2024 at 6:20AM

Monday, January 8, 2024 at 6:20AM

First published in Denmark in 1967; published in translation by Faber & Faber in the UK in 1969; published by Farar, Straus & Giroux (FSG Originals) on January 9, 2024

Termush was “rediscovered” by Faber editors who dug through the Faber vaults to find forgotten novels that might deserve to be regarded as classics. Faber released it in the UK in 2023 as part of its “Faber editions” series.

Termush is the name of a remote hotel on an unidentified ocean. The narrator paid a substantial sum for a guaranteed spot in the hotel as a shelter from catastrophe. His lodging includes access to underground shelters, stored provisions, uncontaminated water, and security against outsiders. The hotel’s luxury yacht is berthed nearby, providing egress if life in the hotel becomes unsustainable.

We aren’t given the details, but a disaster (presumably a nuclear war) gave the wealthy guests reason to check into the hotel. The guests are finally free to venture outside, subject to radiation warnings that send them scurrying back to the shelters. There is little to see; vegetation has gone up in flames, birds are dying.

The novel is intentionally surreal in its depiction of hotel guests as largely undisturbed by disasters that don’t immediately affect them. Perhaps the world outside their walls has nearly come to an end, but they are still able to order dinner from a full menu. The guests display little curiosity about the world’s fate. Occasionally returning to underground shelters when the wind brings too much radiation to the hotel grounds is inconvenient, but most guests are content to follow the directions of hotel management.

The hotel staff is sending out reconnaissance parties to look for inhabitable areas, but their radioed reports are censored before reaching the guests. The narrator opposes the censorship; he wants to know what is left of the world. Management isn’t sure the guests can handle the truth. Most guests seem to feel the same way. If the news is bleak, they don’t want to know.

The narrator understands when a guest who can no longer tolerate “this closed compartment cut off from the world” flees from “the game of make-believe that nothing had happened.” Eventually, a few more follow the path of freedom, leading hotel management to act more like jailers than servants. Perhaps an insurrection is coming.

When survivors appear in search of food and medical care, the hotel guests consider whether it is appropriate to be charitable. The survivors come bearing news of the outside world, which is a good thing, but the outsiders didn’t pay a fee for the hotel’s protection, as did the guests. The guests quickly vote on rules that allow a few survivors at a time to enter the hotel for food and water, but only for one night. This leads to a discussion about the perils of democratic decision-making.

Nor do some guests want their reconnaissance teams to be helping survivors. That’s not the job they’re paid to do, after all (payment presumably meaning continued access to the hotel and its resources), so most guests feel the team members should set their humanity aside and do what they’re told. Termush illustrates the divide between ruling class and working class with more flair than Marx.

The narrator develops an intimate friendship with a woman named Maria, but she is an enigma. She never seems to speak, communicating by expressions that convey her emotions. “She keeps close to me, follows me almost stride for stride, as if this were an order.” I was left wondering whether Maria actually exists.

Much of the time, the narrator seems to be in the dark about the world he now inhabits. Hotel management attributes a guard’s injured arm to being “careless with a hand grenade.” Why does hotel security have hand grenades and what did the careless guard intend to do with his? They later morph from “security” to “soldiers” in ways and for reasons that the narrator does not explain. Eventually, the hotel seems to be under siege, but by whom? The narrator refers to “the strangers” and “our adversaries,” later designating them as “the enemy,” but seems to have no clue about their identity. Nor does he seem to care. The narrator is so detached, so free from opinions, that the story’s moral questions are left unfiltered. Should the hotel help outsiders? Should hotel “soldiers” kill them? Readers are free to make of these issues what they will.

The story’s surreal atmosphere is illustrated by the final sentence: “Outside the sea is still; there is no darkness and no light.” Without darkness or light, what kind of reality exists? The novel’s ambiguities might explain why the Faber editors regarded Termush as a potential classic. The story could be set in any country, in any time. While the guests are sheltering against drifting clouds of radiation, any other apocalyptic event could as easily be substituted. The story resonates because of its focus on group responses to crisis and how those responses may be a function of social class.

RECOMMENDED

TChris |

TChris |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Denmark,

Denmark,  Sven Holm in

Sven Holm in  Science Fiction

Science Fiction