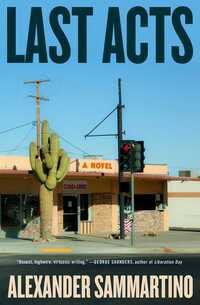

Last Acts by Alexander Sammartino

Wednesday, January 17, 2024 at 7:14AM

Wednesday, January 17, 2024 at 7:14AM

Published by Scribner on January 23, 2024

Last Acts is built on dark humor. Some of the humor derives from unlikely sources. Drug addition isn’t funny. Neither are school shootings. Everyone survives the shooting in Last Acts (the headlines speak of Mass Survival rather than Mass Murder) because the gun was too big for the shooter to handle. He fell down sobbing without managing to kill anyone.

Sobbing is a common experience in Last Acts. So many events in life promote tears. Look at the same events from a different perspective, however, and they might promote laughter. Drug addiction isn’t funny but people in rehab might be. School shootings aren’t funny but a survivor who forms a support group for victims of Mass Survival might give readers a reason to laugh. Marketing isn’t funny but, well, sure it is. How perspective influences attitude is an important theme of Last Acts.

The transition from loser to winner is another of the novel’s themes. It’s a transition that should make people happy, but are winners always happy? They might have been happier when they were losers. Change is the only constant. A loser who becomes a winner will probably become a loser again. But whether the person is really a loser is, again, a matter of perspective. A character named Felicia illustrates the point: “She was happy with her life, more or less. Sometimes the wind hit her and she felt certain she would sob. But more frequent were the days when she walked around smiling, confident that she would never die.”

The novel’s most important characters are Rizzo and his son Nick. Rizzo’s first name is David but he’s known to all as Rizzo. Rizzo has a gun shop in a strip mall that was developed by Buford Bellum, a serial entrepreneur who is at heart a con artist. Rizzo had a history of being fired from sales jobs until he believed Buford’s pitch that buying into the “business park” would guarantee his success. Instead, Rizzo has crushing debt, a store full of guns, and few customers willing to venture into the lonely mall to buy them.

The possibility of an afterlife is the only thing that mitigates Rizzo’s fear of death. When Nick dies from a drug overdose and is brought back to life, Rizzo’s hopes are dashed by Nick’s report that he experienced nothing after he died. Rizzo is terrified by the thought that his miserable life is all he will ever have.

Nick is a heroin addict. He needs drug treatment but, when Rizzo takes him to the most affordable treatment center, his credit cards are declined. Unsurprisingly, the center refuses Rizzo’s request to “just keep him for a for a few days” while Rizzo tries to find the money.

Nick goes to work in Rizzo’s failing gun shop, hoping to prove to his father than he is done screwing up his life. He tries to make a commercial for his father’s store, promoting sales by promising to donate some of their revenues to drug addiction treatment. Nick’s ad libs (“at Rizzo’s Firearms, we are shooting addiction dead”) cause multiple reshoots, but the commercial they eventually produce goes viral, bringing success and more opportunities to screw up. Life is a series of ups and downs. Nick and Rizzo both make the transition from loser to winner before they fall again.

Rizzo’s downfall occurs when he is held responsible (unjustly in the collective view of his gun-happy customers) for the failed school shooting. Nick’s production of the commercial for his father’s store seems to give birth to a career as a marketing consultant until he teams up with Buford Bellum. Neither father nor son can get ahead for long.

Nick and Rizzo love each other, albeit grudgingly. They would like to trust each other, but trust must be earned and neither parent nor child is capable of exercising sound judgment. Their comical mishaps promote guilty laughter (it isn’t nice, after all, to laugh at another’s misfortune). The story develops poignancy from the willingness of father and son to maintain a relationship despite their inevitable disappointment with each other. They can work through their issues because they know they’ll always have each other.

In the tradition of modern (or postmodern or whatever they are these days) novels, Last Acts ends abruptly, in the middle of an important development. That will annoy some readers. I’ve almost gotten used to it. Maybe Alexander Sammartino will write a sequel that explains the next chapters of his characters’ lives. He probably won’t, but I hope he does.

RECOMMENDED

Reader Comments