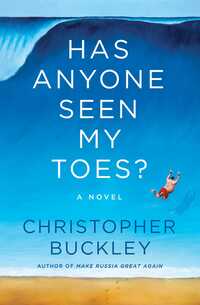

Has Anyone Seen My Toes? by Christopher Buckley

Monday, September 5, 2022 at 7:20AM

Monday, September 5, 2022 at 7:20AM

Published by Simon & Schuster on September 6, 2022

The fear of dementia probably strikes most people as they age, at least those who have a mind they would miss if they lost it. On the theory that humor conquers fear, Has Anyone Seen My Toes? could be a therapeutic read for older readers who wonder whether they should end their lives before they forget the combination to the gun safe.

The nameless protagonist is a writer. He’s staying in a small community in South Carolina, the location of his disastrous movie about patriotic prostitutes during the Revolutionary War (a movie that still sells well in hotel pay-for-views). He’s gained weight during the pandemic. In fact, he put on so much weight he can’t see his toes when he stands on the scale and his I-phone no longer recognizes him (he believes the phone is fat shaming him).

The protagonist’s behavior is becoming increasingly erratic. His wife complains when he sits in the dark at night, prepared to shoot moles that are ruining his yard (he suspects her of siding with the moles). He has started a screenplay that turns out to a version of the movie The Eagle Has Landed, substituting Roosevelt for Churchill. He is certain that he has seen attack ads in an election for coroner, but his inability to recall his conversations about the ads with the candidates suggests that he is suffering from the onset of dementia.

On the other hand, a different sort of mental disturbance might be to blame, one that counts paranoia among its symptoms. The writer is convinced that Putin is trying to sway the coroner’s election and that only he can thwart Putin’s dastardly plan. At the same time, he’s certain that the mortician running against Putin’s favored candidate has been burying people alive. It’s no surprise that the writer visits a psychiatrist before the story ends.

Has Anyone Seen My Toes? is a novel of digressions that magically add up to a plot. The progtagonist is always looking things up. We learn obscure details about Gone with the Wind, Carl Reiner, and celebrity deaths. We learn that Donald Sutherland’s tongue is periodically ravaged by parasites. We learn the etymology of several fun but useless words. We learn about writers who committed suicide. We learn the many reasons why the protagonist (like me) has never been able to force himself to finish reading Proust’s unbearably dull Remembrance of Things Past (or whatever they’re calling it these days).

It might not be politically correct to build a comedy around dementia (or any other disease) but Has Anyone Seen My Toes? is awfully funny. And no spoilers here, but maybe the writer’s problem isn’t quite what it seems. In any event, confronting the fear of dementia with humor might be the best approach to mental health, given the failure of expensive but profitable drugs like Aduhelm.

While the novel’s focus is on the fear of dementia, its humor is wide-ranging. The writer pays $7500 a year for a concierge doctor because, for that price, the doctor won’t hassle him about his bad habits. Christopher Buckley makes fun of the South, “where people start driving at fourteen and by eighteen are competing in NASCAR.” He mocks plantation tourism and its tendency to overlook the slave quarters.

Buckley also has fun with Trump and the far right. The doctor responds to COVID by prescribing whatever drug Trump has most recently mentioned. The writer goes along with it, although he would draw the line at “injecting Clorox or shoving a lightstick up my ass.” And when the writer takes the 5-word memory test that Trump regarded as proof of his genius, he comes up with a 5-word phrase from his screenplay, possible proof that he is even more demented than the last president. Quotations from Mein Kampf illustrate how American propagandists on the right are following Hitler’s advice: tell bold lies, repeat them endlessly, appeal to emotion rather than reason, and wait for weak minds to bow to your authority.

Buckley’s political humor scores bullseyes because he aims at unmissable targets. For the most part, however, the story is apolitical. The pandemic, with its toilet paper shortages and spreading bellies, is the source of familiar humor. By giving his protagonist an addled mind, Buckley takes the story a step or two beyond the familiar, sometimes reaching toward the absurd, but he never has to reach far to get a laugh.

RECOMMENDED