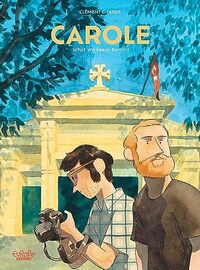

Carole by Clément C. Fabre

Wednesday, August 23, 2023 at 6:33AM

Wednesday, August 23, 2023 at 6:33AM

First published in France in 2023; published in translation by Europe Comics on August 30, 2023

For reasons he never explains, Clément’s life fell apart at the age of 27. His therapist suggested he learn more about his grandparents’ experience in Turkey. They were children during the Armenian genocide and fled after nationalists became violent in the mid-1950s. Perhaps Clement is suffering from intergenerational trauma. Perhaps his crisis is one of identity. He doesn’t feel like an Armenian. He doesn’t feel like a Turk. France is the country of his birth but he doesn’t seem to feel French.

Before his grandparents moved from Istanbul to France, they had a child named Carole who died in infancy. Clément’s grandmother later tried to locate Carole’s grave but discovered that the grave is missing. In need of a vacation and perhaps for its therapeutic value, Clément and his brother Robin decide to find Carole’s grave. Robin also wants to make the trip to further his study of history.

The brothers arrive in Istanbul during the Gezi Park protests. They search a cemetery, and then several more, taking pictures of headstones that are represented as drawings in the graphic novel. They can’t find Carole in any death registry. They visit and photograph places that were important to their grandparents: the church where they married; a court where their grandfather played basketball; an apartment building where their grandmother lived; their grandfather’s school and the place where he had his shop.

The brothers discover that Turkey is divided between nationalists who support Erdoğan and those who want the country to accommodate Kurds and Islam. Clément plans to create a graphic novel about their journey. To that end, he draws the scenery: beautiful old buildings, lovely landscapes, but also the aftermath of riots and buildings covered with graffiti. The brothers are also a bit divided, both in their willingness to try local foods (Clément finally relents and enjoys his brother’s culinary suggestions) and in their dedication to solving the mystery of Carole’s missing grave.

When the trip seems incapable of solving the mystery of the missing grave, the brothers wonder whether the trip was worthwhile. Perhaps the journey was more important than the destination. Traveling to Istanbul gives them a reason to think more carefully about their grandparents’ stories and their own ancestral identities. They don’t understand why their grandfather has nothing but fond memories about a country that slaughtered his ancestors, forced him to forget his language, and made him change his name so he would fit in with Turks. Their fascination with their grandfather’s story shortchanges their grandmother’s history. Their mother, on the other hand, seems wary of disturbing her parents with new discoveries about their past.

The story is mildly frustrating in that the facts that the brothers learn, both before and during their trip, don’t quite match the details of their grandfather’s explanation for leaving Turkey. Those discrepancies cry out for an explanation but none is forthcoming. I suppose the story is autobiographical and the author can’t explain what he doesn’t know.

Otherwise, the story is informative. Using narratives, headlines, and drawings of old photographs, the book provides a history lesson of Turkish nationalism and its impact on Armenians and Greeks. At times, the story seems like it is told by a relative who is showing slides of a family vacation (although these days, I suppose slides have been replaced by digital photos or videos that are displayed on the family’s widescreen TV). The travelogue might be more meaningful to the person telling it than to the audience.

The art and coloring are effective but familiar. Had Carole followed a mystery to a solution, it would have been a more gripping story. On the other hand, it is packed with important information about a part of the world that is probably a mystery to most Americans. For that reason, Carole is worth an inquisitive reader’s time.

RECOMMENDED

TChris |

TChris |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Clément C. Fabre,

Clément C. Fabre,  France,

France,  Turkey in

Turkey in  Graphic Novel

Graphic Novel